They Said No

Encounters with Kuwaiti Educator using AI in Kuwait Science Education

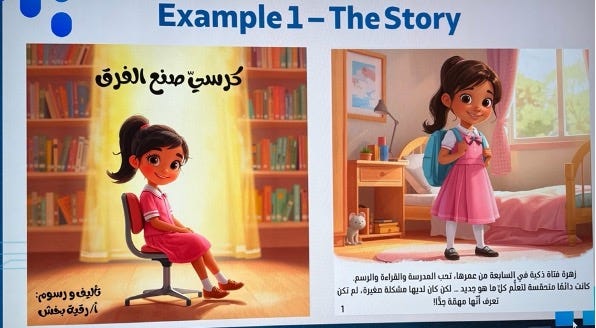

A teacher, working with the youngest learners in Kuwait, became the go-to for the whole programme. Not just her peers — teachers and lecturers came to her when they got stuck using AI tools. She’d published a little book for her pupils, created with GenAI: The Chair That Made a Difference. The story of a little girl whose bad posture — caused by a poorly fitting school chair — led her to co-design a techno-chair that warned her when she slouched in class. Her back pain got better. And classmates with bad backs also got given a chair that made the difference.

It was a very simple and short illustrated story. This and a particular conversation stopped me in my tracks. It’s why I’m writing this.

From the Chair that made a Difference by Roukaya Bakhsh

Over the past months, I worked with the Cambridge Partnership for Education on a three-month AI for Science Educators programme, commissioned by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Science (KFAS). We opened with a three-day residential at Kuwait University in November, working with 50 selected participants. This was followed by the online part of the course programme, supported by four 45-minute coaching sessions. Two and a half months later, we were back in Kuwait for an intense four-day programme.

Kuwait University

What made the different wasn’t the bespoke curriculum we developed for this programme. It was the context in which the programme was delivered. We worked in the national Kuwaiti education context, rooted in its own curricula, culture, language and local education priorities. Working within the Kuwaiti context meant we couldn’t default to familiar ground. We had to tune in — to the culture, to the perspectives, to what AI meant in this specific setting. That raised our bar. And it taught us more than one lesson.

We engaged with educators across the full education spectrum, from Kindergarten through to university. Educators from each level challenged one another in ways that simply wouldn’t happen within a single cohort. It was unusual. It was enriching.

The Kindergarten and Primary teachers were the ones who surprised us most. They navigated the AI tools with a creativity and problem-solving instinct that was frankly humbling. They created resources for their pupils, shared them with peers, built Instagram groups to keep learning and inform their peers on the good and practical use of AI. They pushed their learning and practice further with every new attempt, every lesson plan, every workflow, every resource.

The teacher behind The Chair also created animations to help her children distinguish carnivores from herbivores. Her goal was never to just put screens in front of children; AI was the tool to bring enrichment and augmentation to her classroom. And she was more than keen to share what she’d learned, with grace and inspiring humility.

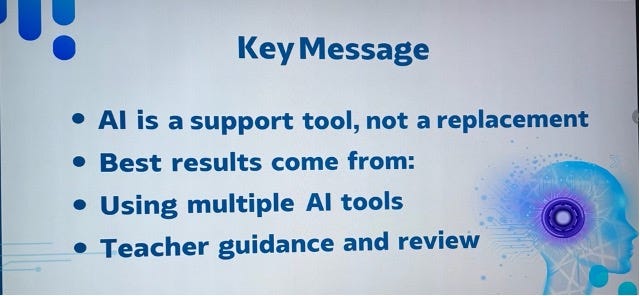

Key Message: AI for augmentation, guided and reviewed by teachers

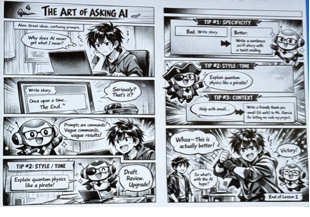

At secondary and university level, educators created resources to explain scientific concepts, including a comic strip on using GenAI effectively, built around the Art of Asking AI for students studying Quantum Mechanics, rather than simply offloading one’s thinking to the machine.

The Art of Asking AI: to support students to understand concepts of

Quantum Mechanics as well as teaching mindful use of AI

But something else emerged. Something that didn’t surprise me but highlighted a fundamental shortcoming of GenAI. One that should remind all of us, especially when using AI in education contexts.

During the last session with Kindergarten and Primary teachers, we continued a conversation about using GenAI and LLMs in Arabic. Using the most prominent AI LLMs’s, teachers often had to prompt in English to get usable results, before translating the content. When they used Arabic for prompting, the output felt like a translation, not content generated in Arabic in the first place. The grammar was off. The phrasing and often words, sounded strange. We couldn’t prove that LLMs were looking at English language data, prior to translating the output into Arabic, but we did suspect this might be the case. I told them I had seen similar results working with AI in other non-English languages. A sense of non-native origination was shared and reflected upon. What did that mean for their context, the culture and the learners in their schools or universities? I explained to them that I had the same experience using AI in non-English languages.

Then came the moment that brought everything together for me.

During one of their presentations, AI-generated images were displayed and discussed. I asked the teachers whether they felt the images represented them, the children in the classroom or their cultural context and references. Could they recognise themselves and their pupils in what had been generated?

The answer was unanimous.

No.

This opened a conversation about bias that went to the heart of what we’d spent three months working on together. The language models these educators were using did not draw on Arabic LLMs, but tended to be typically ChatGPT and Gemini. Co-pilot was also often used as Microsoft technologies are ubiquitous in education settings in Kuwait. The results of using these models did not represent Kuwaiti language, culture, context or their visual world. We were being confronted by the WEIRDness¹ of AI, a result of these go-to AI systems still predominantly being developed by Western, English-speaking white males in their contexts or originate in China.

For me, everything discussed during the programme somehow culminated in that final conversation. A shared recognition of how far GenAI still has to evolve to become more representative, inclusive and equitable. The message hit home.

¹ WEIRD — Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic — a term used to describe the narrow demographic from which much of AI’s training data and development still originates. This acronym was coined by the anthropologist Joseph Heinrich of Harvard University. He developed the WEIRD framework to raise people’s consciousness about psychological differences and highlight that WEIRD frameworks represent a rather thin slice of humanity’s cultural diversity. For Henrich, WEIRD accentuates the sampling bias present in studies conducted in cognitive science, behavioural economics, and psychology.

For those of you interested in the WEIRDness of AI, read this post on my Substack: https://www.trainofthought.me/p/the-weirdness-of-generative-ai

With thanks to the KFAS team, who managed the full logistics and operations throughout; to Niall McNulty of Cambridge University Press and Assessment, Ismail Sabry, Cambridge Partnership for Education; Educate Ventures, led by Madiha Khan and to Carmen Thomas, Kristina Cordera, Ali Chaudry and Jennifer Seon.

The "Said No" moment captures something crucial. When AI-generated content doesn't reflect the learners' actual cultural context, it's not just a tech issue but an epistemic one. Arabic prompts producing output that feels translated rather than natively generated shows how anchord these models are in Western data. I've seen similiar issues in other non-English contexts where the tool becomes a cultural intermediary that doesn't actually understand the target culture.

Such a powerful piece Carl - and very insightful to all those who want to implement a human, ethical and culturally sensitive AI